Photography by Daniel Vaughan

Kenhteke Seed Sanctuary & Learning Centre’s sacred mission

It was the first bright, spring day of the year, the kind of day that warms your bones and confirms you have survived another winter. It was April 22, Earth Day 2019, my mother’s birthday, and Easter Monday - the last day of the holiest of weekends for the Catholic Church. I was driving east on Highway 2 which turns into Princess Street at Kingston’s western most boundary. My destination was about halfway downtown.

Although impressive stone gateposts mark the entrance, the Sisters of Providence of St. Vincent de Paul is easy to miss. Most of the property, the winding driveway leading to the Motherhouse surrounded by about 30 acres of a park-like setting with an old barn tucked in behind, can’t be seen from the road. The Sisters had graciously opened their home today for a ceremony. After two decades as the home of the Heirloom Seed Sanctuary, the seeds had to move.

For some there was a lot at stake. Over the years the sanctuary had become an integral part of the Kingston area food growing communities, sponsoring such well-known events as local Seedy Saturdays.

The collection was particularly significant for the Mohawks of Tyendinaga, just down the road, as most of the seeds had their origins in Indigenous cultures. In 2017, the decision was made to repurpose the Princess Street property and the seed sanctuary had to close. The ceremony on this sunny, spring day marked a significant point in the journey of these seeds and the cultural survival they embodied, as well as a humble, yet extraordinary, act of reconciliation.

The seeds had come to the Sisters by way of organic farmers, Carol and Robert Mouck, whom after a quarter of a century of farming, had nurtured a collection of 400 heirloom seed varieties of vegetables, flowers, and herbs on their farm near Napanee. Planning to wind down their farming operation, the Moucks approached the Sisters for help saving the seeds. The Sisters took on the task, at first with the help of the Moucks and other volunteers, eventually hiring Cate Henderson fulltime in 2008.

Cate and Janice Brant first crossed paths in 2009 at Queen’s University where Janice was giving a talk on seeds. Growing up on a farm in Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory, Janice had been gardening since she was five years old; her Mohawk name Kahéhtoktha, translates to “she goes the length of the garden.” After this chance meeting with Cate, she often visited the Heirloom Seed Sanctuary, less than an hour’s drive from her Tyendinaga home. Traditional Mohawk food and food ways had always been central to Kahéhtoktha’s work as an educator, artist, and activist. When she learned the seed sanctuary was shutting down she already knew the significance of the collection for her community and saw an opportunity.

“Agriculture is part of who we are as a community and something we are still quite passionate about here. We still have a large agricultural land base. It’s important and people still grow certain plants for food and for our ceremonies.”

Kahéhtoktha knew about 80 per cent of the collection had originated in Indigenous communities, including her own. Settler cultures had acquired them, changed their names, some seeds had been commercialized, even patented, so they could be sold for profit.

The Mohawk are members of the Haudenosaunee, an alliance including the Cayuga, Oneida, Seneca, Onondaga, and later the Tuscarora. While historians and anthropologists still argue over when the alliance originated, they agree they are all matrilineal cultures. Traditionally women hold the knowledge of the seeds and how to grow plants for food, medicines, and sacred ceremonies, passing this knowledge freely on from one generation to the next. For the Mohawks of Tyendinaga, bringing the seeds back would be a rematriation.

Kahéhtoktha wasn’t sure if enough people in her community shared her enthusiasm, so she invited Cate to Tyendinaga to talk about the collection. The response made it clear the interest was there and soon the volunteer group, Ratinenhayén:thos “they are the seed farmers” was formed. After just four meetings Ratinenhayén:thos had a plan approved by the broader community and was ready to meet with the Sisters, now with an even greater sense of urgency because the timeline for moving the seeds had been shortened from five years to two.

“It was a wonderful meeting and we instantly connected with each other because our motivation was not economic, our motivation was spiritual. We told them a little bit about our culture and history. Even our creation story teaches us the first woman brought seeds with her, and those plants still sustain us and our medicines even today. Then the Sisters asked us if we could put it in writing. Of course, being very oral people, we hadn’t even thought of writing a letter so that made us all laugh. The Sisters were looking around the room wondering what was so funny.”

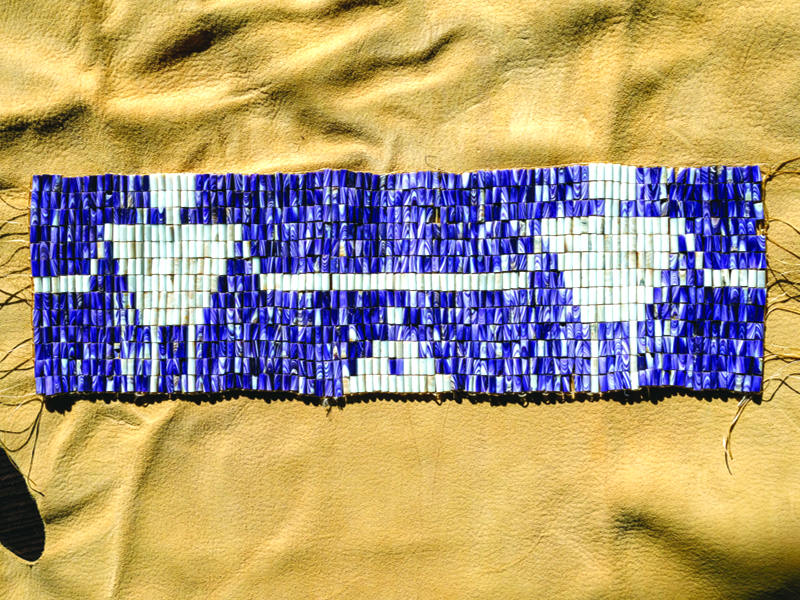

The Sister’s request could have been a roadblock but Ratinenhayén:thos came up with an even more meaningful process, conceptualizing the first modern day Wampum belt and inviting the broader community to help make it. Wampum belts are a traditional Haudenosaunee way of telling stories or documenting agreements such as treaties between nations. This Wampum belt was made using traditional beads made from Quahog shells to form the symbols in a style used as far back as anyone knew.

“We went from this place of the Sisters asking us for a letter of intent, to entering an agreement with this Wampum belt. Now we’re making this promise together, not really by writing it down but by promising each other this is how we will do it.”

More than 100 people gathered in the basement of the Sisters of Providence of St. Vincent de Paul Motherhouse on this Easter Monday afternoon. The Sisters decided to pass the seeds on to two groups - the Kingston Area Seed System Initiative - a group of farmers, gardeners, and community members promoting sustainable and healthy food practices - and Ratinenhayén:thos. The Sisters also agreed to pay Cate’s salary for two years to help both groups succeed with the transition. The Passing of the Seeds Wampum belt depicting all of this was front and centre for all to see. Speeches in English and Mohawk were followed by music and traditional drumming, and the Sisters passed symbolic envelopes of seeds to their new caretakers. The mood overall was celebratory, and the event ended with a lunch of locally sourced food including traditional Mohawk dishes.

“The rematriation is a beautiful act of reconciliation for us as Indigenous people. I feel strongly it’s not like other forms of reconciliations we’ve heard about. It’s different. For me this feels truer because they’re not just saying here are the seeds that were once taken, now we’re giving them back, but they also want to help make the transition successful.”

On another sunny day, this time in October, not quite six months after the rematriation ceremony, about 50 people gathered in a 15-acre hay field on Tyendinaga’s York Road. Surrounded by trees just starting to show their fall colours, this was the land the community had allocated to Ratinenhayén:thos. A path at the back of the field leads directly to the community offices, not far from the library housing the newly formed Kenhte:ke Seed Sanctuary and Learning Centre and the Passing of the Seeds Wampum belt. It was a weekend morning, children were running around enjoying the open space, older people had come too, out of curiosity and to get some gardening tips, and Ratinenhayén:thos members were there to witness the first seed harvest. As the group gathered around the raised garden beds, Cate pointed out flowers planted to attract pollinators and a bed of sweet grass grown for ceremonies. Cate was there to show everyone how to harvest tomato seeds to be followed by a sampling of salsa made from freshly picked tomatoes.

Emma Brant-Edwards was there that day. A student at Eastside Secondary in Belleville, Emma was a Ratinenhayén:thos member from the beginning. “I’ve gardened all my life,” she said. “I just like learning about how my seeds grow. Some seeds are specific to the Mohawk culture and if no one plants them and saves the seeds there’s not going to be any for the people in the future.”

Ratinenhayén:thos has had a busy couple of years and Kahéhtoktha anticipates many positive spin-offs to their work. More people will have access to seeds to grow their own food, and plants not harvested for seeds can be used in the community’s diabetes or school food program. Perhaps the greatest impact will be cultural. As research traces the origins of seeds now called Jacob’s Cattle bean, or Dutch Brown bean, for example, they will be given back their original names and knowledge of the Mohawk language will grow, too. “We can’t separate the seeds from who we are. If there is any way we could plug the language into something it’s through agriculture because the words already exist. If we were teaching a computer class, we would have to invent words. For this we don’t have to invent words, they already exist, and are part of the core of the language.”

It has been more than a year now since the Easter Monday ceremony. The field on York Road is coming to life. A modest sign marks the Ratinenhayén:thos site, soon to be replaced with a much larger one, thanks to a donation from Drystone Canada and Topsy Farms, two of many private donations to the project so far. The sign will mark the site of the first, and so far, only Indigenous owned and operated not-for-profit seed sanctuary growing live seeds in Canada.

The second crop of garlic planted last fall has sprouted and more beds are growing, even with the complications of social distancing, thanks to volunteers who responded to the Kenhte:ke Seed Sanctuary and Learning Centre’s call for help with spring planting. Soon the Passing of the Seeds Wampum belt will be brought out to renew the commitment from volunteers like Emma to nurture the plants, save the seeds, and pass on the knowledge. With little fanfare an act of reconciliation has taken place here and the seeds have found their way home.